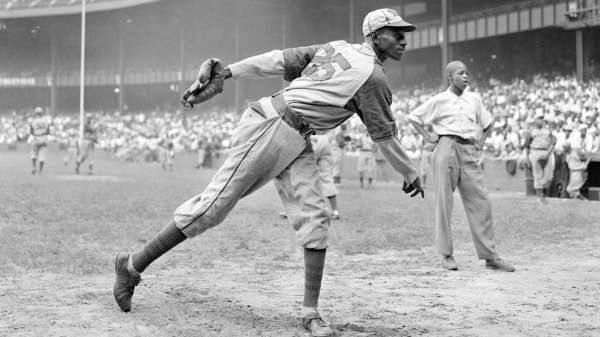

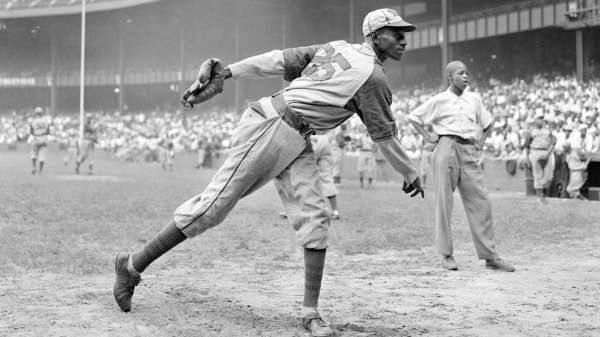

Kansas City Monarchs pitcher Leroy Satchel Paige warms up at Yankee Stadium in 1942 before a Negro League game between the Monarchs and the New York Cuban Stars. Matty Zimmerman/AP CNN —

Have you ever heard something on the news and responded by saying “it’s about darn time?” That’s how I felt when I heard about the integration of Negro League Baseball (NLB) statistics from 1920-1948 into Major League Baseball’s (MLB) record books.

This move doesn’t somehow “erase the years of injustice,” as the documentary “When It Was A Game” put it. Rather, including NLB statistics in the MLB ones “serve[s] to remind us of what we missed” by having racially segregated leagues.

Indeed, as elite sportswriter Neil Paine pointed out to me, it’s the stats that show us that the NLB was the equal of, if not superior to, its White counterpart.

Consider the statistics of when nine White major leaguers from various teams – who came together under the banner of “all-star” teams – played against teams of Black major leaguers.

The NLB players won 51% of the time from 1900 to 1948. This isn’t some statistical fluke, either. We have 180 documented games during this stretch, which is the equivalent of over one season of major league games (162 currently) or more than 25 World Series taken to the maximum of seven games.

As Negro League historian Todd Peterson noted when he made his case a few years ago, the Negro Leaguers were the only ones to consistently beat White major leaguers, who dominated squads of semi-pro, college and minor leaguers.

Satchel Paige (L) and Dizzy Dean at an exhibition game at Wrigley Field in Chicago, comparing grips in 1947. Mark Rucker/Transcendental Graphics/Getty Images

The games between White MLB stars and NLB players left a lasting mark on Hall of Famer Dizzy Dean, who had organized a lot of games between White “all-stars” and Negro League players. Dean had great respect for the skills of arguably the Negro League’s best pitcher, Satchel Paige, after Dean’s team of White ball players fell to NLB teams on numerous occasions.

While players like Paige eventually did join an integrated MLB, he was well past his prime. Fortunately, we got to see other NLB players join an integrated MLB a short time into their careers.

Willie Mays was the best player of the second half of the 20th century, according to the all-encompassing stat wins above replacement (WAR); Mays was a member of NLB’s Birmingham Black Barons in 1948.

Henry “Hank” Aaron was the second-best player, according to WAR, of the second half of the 20th century. The 20th century home run king was a member of the NLB’s Indianapolis Clowns in 1952, after the period where NLB teams were considered major league for stat counting purposes.

High-level players and deserved accolades

It’s depressing to imagine a world where Mays or Aaron didn’t play in the integrated major leagues, which is true for Black players overall. They quickly became an integral part of the American and National Leagues in the late 1940s, 50s, 60s and 70s. Black players were on average the best players, which adds to the case that the NLB was a major league.

Willie Mays of the New York Giants slides safely into the plate on Wes Westrum’s bases-full single in the sixth inning against the Philadelphia Phillies at the Polo Grounds, New York. Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Former NLB players who joined the integrated MLB got on base more frequently (.361) than the average (.324). They hit for more power too with a higher slugging percentage (.455) than the average (.380).

The same dominance of former NLB players held true for pitching in the integrated MLB. They won more games (55%) than the average major leaguer (50%), gave up fewer runs (with an ERA of 3.76 vs. 3.91) and struck out more players per nine innings (5.91 vs. 4.89).

It’s not surprising that the second former NLB player to win Rookie of the Year in the integrated major leagues was pitcher Don Newcombe. In fact, former NLB players won the National League Rookie of the Year every year from 1949 to 1953.

The first MLB player to win Rookie of the Year in the integrated league was Jackie Robinson.

Jackie Robinson broke Major League Baseball’s color barrier in 1947, when he took the field for the Brooklyn Dodgers on Opening Day. Hulton Archive

Robinson, second from left, poses with his siblings and his mother, Mallie, for a family portrait circa 1925. Robinson was born in Cairo, Georgia, but raised in Pasadena, California. Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Robinson was a formidable athlete in college, lettering in four sports at UCLA. He led the nation in rushing as a football player. After college, Robinson was drafted by the US Army and spent a couple of years in the military. Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Shortly after he was discharged by the military in 1944, Robinson was signed by the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro Leagues. Sporting News/Getty Images

Robinson signs a contract with the Montreal Royals, a minor-league team and farm team of the Brooklyn Dodgers, in 1945. Archive Photos/Getty Images

Robinson married Rachel Isum in Los Angeles in 1946. Throughout his life, she was his partner and sounding board, a steady companion when he was the subject of criticism and worse. Archive Photos/Getty Images

Robinson crosses home plate after hitting a three-run home run for the Montreal Royals in 1946. BettmannGetty Images

Young Dodger fans reach down to try to get Robinson’s autograph during an exhibition game in New York on April 11, 1947. Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Robinson poses in the dugout with Dodgers teammates as he makes his historic debut on April 15, 1947. With Robinson, from left, are Johnny “Spider” Jorgensen, Harold “Pee Wee” Reese and Eddie Stanky. Photo File/Getty Images

Robinson played several positions for the Dodgers: mainly second base but also third base, first base and a little outfield. Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Dodgers executive Branch Rickey was integral in bringing Robinson to the majors. Rickey had been scouting players who could break the color barrier, and he was looking for someone who would be able to endure the racial hatred and not lash out in anger. “Are you looking for a Negro who is afraid to fight back?” Robinson reportedly said. Rickey responded that he was looking for someone who had “the guts not to fight back.” Transcendental Graphics/Getty Images

Robinson and Dodgers teammate “Pee Wee” Reese cook soup with their children in 1950. Reese was a big Robinson supporter, especially during that difficult first season. When some teammates wanted to boycott Robinson’s addition to the team, Reese refused to sign the petition. And as the story goes, Reese once put his arm around Robinson’s shoulders in the middle of a road game, embracing Robinson as he was being heckled. Rogers Photo Archive/Getty Images

Robinson leaps into the air to try to turn a double play in 1952. Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Robinson steals home during Game 1 of the 1955 World Series. The Dodgers lost the game but went on to defeat the New York Yankees in seven games. Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Robinson shakes hands with President Richard Nixon at a GOP rally in 1960. Robinson attended the 1964 Republican Convention, but he later supported Democrats as the political parties’ makeup changed. Paul Schutzer/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

From left, Edd Roush, Robinson, Bob Feller and Bill McKechnie stand with their plaques after being inducted to the Hall of Fame in 1962. Cliff Welch/Icon Sportswire/Getty Images

Robinson appears on “The Ed Sullivan Show” in 1962. After retiring, Robinson became an executive for the Chock Full o’Nuts coffee company. He also spoke out on civil rights. CBS Photo Archive/Getty Images

Robinson and his wife, Rachel, pose with their three children — Jackie Jr., David and Sharon — at their home in Stamford, Connecticut, in 1962. AP

Robinson works in the broadcast booth during the 1960s. Robert Riger/Getty Images

Robinson attends a meeting for Freedom Marchers in Williamston, North Carolina, in 1964. He was there to lend his name to the integration efforts in the city. Bettmann/Getty Images

Robinson signs autographs before the start of an Old Timers Game in Anaheim, California, in 1969. Three years later, he died of a heart attack at the age of 53. Bettmann/Getty Images Jackie Robinson's life in pictures Prev Next

Sometimes lost in all of the deserved accolades of Robinson’s breaking the color barrier in 1947 was just how good he was as a player in the integrated league. He put together seven of the best seasons ever for a guy who primarily played second base, according to WAR. Robinson did this while not playing a single integrated MLB game until he was 28, when many players’ skills are already declining.

Players like Robinson and Larry Doby – the first American League Black player and Hall of Famer – were able to perform at a high level, despite having to put up with a lot of racist rhetoric from fans and fellow players.

Sadly, some NLB stars never got to play in an integrated MLB: catcher Josh Gibson was one of them. He died before Robinson ever took the field for the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947.

Baseball catcher Josh Gibson in an undated photo. AP

With Wednesday’s news, Gibson’s now credited with being the all-time baseball leader in batting average at .372 and power hitting (with a slugging percentage of .718). Gibson also leads in on-base-plus-slugging (OBPS) at 1.177, which combines getting on base and hitting for power. Ty Cobb had led the first category, while Babe Ruth led the second and the third.

Gibson’s great grandson put it best when he told CNN that “now, the conversation begins where Josh Gibson ranks as the greatest of all time or one of the greatest of all time.”

It’ll be a fun debate to compare the power hitting of Gibson and Ruth. We’ll never know how Ruth would have batted if Black players were part of the American League, or how Gibson would have done in regular season competition against White players.

But what’s interesting about the MLB is that it was already combining records for two totally different leagues prior to adding the NLB to the record books.

Larry Doby, center fielder of the Cleveland Indians, hits a home run in his second season in 1948. The Stanley Weston Archive/Getty Images

The American League (of which Doby was part of) and National League (of which Robinson was part of) didn’t play regular season games against each other until 1997. Cobb never played against a NL squad in the regular season. Ruth only did for well less than half a season, after he was well past his prime.

In fact, if you were to look at the leaderboard for White MLB stats prior to integration, you’ll see many players never played the opposing league in the regular season. NL pitcher Grover Cleveland Alexander never played against the AL. AL pitcher Walter Johnson never played against the NL.

A big reason for that is that it was basically impossible for the AL and NL teams to trade players to each other prior to 1959. The leagues were so distinct that they had different presidents just like the NLB.

What today’s MLB did in combining the records of the different leagues – the AL, NL and NLB – makes sense and has precedent to some degree. When people look at MLB stats now, they’ll get a truer picture of who was good, great or transcendent, regardless of which league they played in.